We are familiar with the men of the Joseon Dynasty, especially the kings and the famous figures since their names were recorded in the Annals of Joseon Dynasty, but for the women during that era, not many facts were known about them. I think it’s good to introduce some facts about the women of Joseon Dynasty, especially their ranks and their roles in the society. The women lived according to their spouses’ ranks and in some circumstances, their social statuses also depended on their line of job, such as court ladies and entertainers. I have written two posts; one about the general settings of Social Strata in Joseon Dynasty and another one about Royal Titles and Styles in Joseon Dynasty. These two posts might give you a good introduction before you continue to read this post. But there’s no pressure, if you want to know about the women first, then let’s get dizzy together with this one~

I have decided to split the original post into two parts since it turned out to be quite long. This part focuses on the women of the royal family and the aristocrats.

Women’s life during Joseon Dynasty took a different turn due to the country adapting neo-Confucianism, which changed the nation into a patriarchal society that focused on the men. In the history of Korea, women were once given the opportunity to be the queens regent who reigned in their own names, for instance Queen Seondeok of Silla. Although the women of Joseon Dynasty lived in the restricted patriarchal system, some of them managed to make their names known to the whole nation and they continued to be remembered until today. Although the women were not given the opportunity to hold government posts and they were not allowed to interact freely with men outside their family circle, they wielded power in their own rights and showed their contributions in building the nation.

Royal Family

Queen and Queens Dowager

Royal family was at the top hierarchy of the Joseon people, with the King as the ruler of the nation. With her husband as the country’s king, a queen consort or wangbi (왕비, 王妃) was the Mother of the Nation, who was the most important woman in the royal household as well as the whole nation. A queen was highly regarded as a virtuous woman and a role model for the women below her. Hence, the journey to become a queen was not short and easy.

A queen gained the status through the appointment of her spouse as the king. Most of the time, the queen was first married to the heir of the throne as Royal Princess Successor Consort or wangsejabin (왕세자빈, 王世子嬪). The selection process was rigid, beginning from the marriage prohibition for the whole country in order for suitable candidates to be picked among the young girls of suitable age. The crown princess-to-be was usually from the yangban or noble class and the candidates would undergo a screening process before advancing to three stages of selection process. Some of the basic rules to be qualified as the candidates were:

- the candidate could not be a female member of the Yi clan (meaning that the candidate must not have the same surname as the royal family which was Yi (이, 李), or a close relative of the crown prince, or a person within the eight cousins of the crown prince;

- both of the candidates’ parents must be alive;

- the candidate must have a clean family background (not associated with any case of misconduct e.g. treason);

- the candidate possessed the virtues that fitted the decorum of a crown princess and a future queen;

- the candidate had a pleasant appearance.

The final stage would have three candidates remained after the selection process and the crown prince’s consort would be picked through this final stage. The consort would then undergo a series of training about the etiquette of the palace and education related to her future roles as the crown princess and the queen before getting married to the crown prince.

A queen was expected to bear the legitimate heir to the throne but she won’t simply lose her seat if she happened to be unable to do so. Concubines would be selected and the queen was given the authority to become a mother to the concubines’ children. In certain cases, the queen would adopt the sons of concubines as her own. If the son ascended the throne later after his father the King died, the queen who was still alive would be given the title Queen Dowager or daebi (대비, 大妃). The queen dowager would be given the responsibility to become the regent in the king’s place if the king happened to be too young to rule on his own. The queens dowager continued to live in the palace even after their spouses’ deaths and they wielded power in the court since they were the respected by the court as the elders of the royal family. In certain cases, the families of the queen and queens dowager were powerful and became important political figures because of their connection to the most important women in the country. For the former queens consort who were more senior than the queen dowager, they would be bestowed the title Royal Queen Dowager or wangdaebi (왕대비, 王大妃) and Grand Royal Queen Dowager or daewangdaebi (대왕대비, 大王大妃), with the latter being more senior than the former.

King Sukjong’s first three Queen Consorts as portrayed in the drama Jang Ok Jung, Live in Love (from left): Queen Inkyung was the Crown Princess before she became the queen. After she died, Queen Inhyun was chosen to become the consort, directly ascending to the queen’s position. Jang Ok-jung, on the other hand, was a royal concubine who was chosen as the queen after Queen Inhyun was deposed in the event of Gisa Hwanguk but Lady Jang was demoted back to the rank of Hui-bin when Queen Inhyun was reinstated in the event of Gapsul Hwanguk.

King Sukjong’s first three Queen Consorts as portrayed in the drama Jang Ok Jung, Live in Love (from left): Queen Inkyung was the Crown Princess before she became the queen. After she died, Queen Inhyun was chosen to become the consort, directly ascending to the queen’s position. Jang Ok-jung, on the other hand, was a royal concubine who was chosen as the queen after Queen Inhyun was deposed in the event of Gisa Hwanguk but Lady Jang was demoted back to the rank of Hui-bin when Queen Inhyun was reinstated in the event of Gapsul Hwanguk.

The queen was responsible for the women’s affairs in the palace. A body, known as naeoemyeongbu (내외명부, 內外命婦), was directly under the queen’s supervision, aiming to control the palace women’s affairs as well as organizing ceremonies for the female members of the royal family. The queen held supreme authority of naeoemyeongbu that even the king couldn’t interfere with the matters regarding the palace women, except for extreme cases such as treason. The body was divided into two separate divisions, which were naemyeongbu (내명부, 內命婦) or the Bureau of the Inner Court Ladies, and oemyeongbu (외명부, 外命婦). Naemyeongbu consisted of the royal concubines, crown princess, the crown prince’s concubines, and the court ladies while oemyeongbu was made of the princesses, the queens dowager, the children of the crown prince, the wives of other royalties, and the wives of the government officials.

Naemyeongbu

The queen was the supervisor for naemyeongbu, overseeing the division that consisted of the women who lived most of their lives inside the palace. She was no doubt in the top position among the wives of the king and supervised the royal concubines as well as the other female members of the royal family.

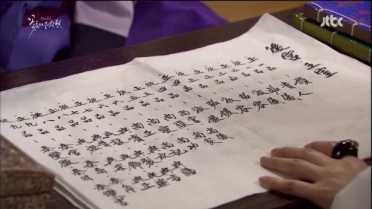

A list of the available ranks for the women in the court, ranging from the 1st senior rank on the right to the 9th junior rank on the left as featured in the drama Cruel Palace: War of the Flowers.

A list of the available ranks for the women in the court, ranging from the 1st senior rank on the right to the 9th junior rank on the left as featured in the drama Cruel Palace: War of the Flowers.

Royal Concubines

The royal concubines or hugung (후 궁, 後宮) were the women selected or favoured by the king to become his concubines. The selection of these concubines took place when the queen couldn’t bear a son to become the heir to the throne and there were also concubines that were originally the court ladies who received the grace from the king, giving them the chance to be part of the king’s harem. The ranks of the royal concubines were as follows:

- 1st senior rank – Bin (빈, 嬪)

- 1st junior rank – Kwi-in (귀인, 貴人)

- 2nd senior rank – So-ui (소의, 昭儀)

- 2nd junior rank – Suk-ui (숙의, 淑儀) ~ the first rank for a selected concubine

- 3rd senior rank – So-yong (소용, 昭容)

- 3rd junior rank – Suk-yong (숙용, 淑容)

- 4th senior rank – So-won (소원, 昭媛)

- 4th junior rank – Suk-won (숙원, 淑媛) ~ the first rank for a favoured concubine who was once a court lady

A concubine would get the chance to rise through the ranks by three means: 1) Becoming the object of the king’s affection; 2)Bearing a son for the king; and 3) Fostering a good relationship with the Queen through the years of staying inside the palace for getting a recommendation to be elevated to a higher rank. Bearing a son for the king would be the fastest route to be elevated and if the son was picked to be the crown prince, the birth mother would be appointed to the highest rank for the royal concubine, which was bin. The bin and kwi-in had the authority to make decisions alongside the queen, making them the closest advisers to the queen. The concubines with the rank kwi-in had sons that weren’t the heir to the throne, similar to so-ui and suk-ui, but had higher position than the other two. So-yong and suk-yong were responsible for the ancestral rites’ preparation and also reception of the guests. So-won and suk-won managed the weaving work related to the fabrics such as linen.

Lady Seong Ui-bin was the royal concubine of King Jeongjo and she was initially a gungnyeo or palace maid. She was elevated to the rank of sanggung after she received His Majesty’s grace before raised to the rank of So-yong after giving birth to Prince Yi Hyang. When her son was appointed as the Crown Prince, she was elevated to the rank bin with the prefix Ui. Han Ji-min portrayed Lady Seong in Yi San.

Lady Seong Ui-bin was the royal concubine of King Jeongjo and she was initially a gungnyeo or palace maid. She was elevated to the rank of sanggung after she received His Majesty’s grace before raised to the rank of So-yong after giving birth to Prince Yi Hyang. When her son was appointed as the Crown Prince, she was elevated to the rank bin with the prefix Ui. Han Ji-min portrayed Lady Seong in Yi San.

Crown Princess and Crown Prince’s Concubines

Crown princess was the most superior among wives of the crown prince but her position is lower than the queen in naemyeongbu. She was the supervisor for the crown prince’s palace, especially the crown prince’s concubines and the court ladies working there. The ranks of the crown prince’s concubines were lower than the royal concubines of the king. The ranks were:

- 2nd junior rank –Yangje (양제, 良娣)

- 3rd junior rank – Yangwon (양원, 良媛)

- 4th junior rank – Seunghwi (승휘, 承徽)

- 5th junior rank – Sohun (소훈, 昭訓)

Court Ladies

Court ladies or gungnyeo (궁녀,宮女) were the working women inside the palace. The word gungnyeo literally means ‘palace women’ and it was derived from the term gungjung yeogwan (궁중 여관) which gives the literal meaning ‘lady officer of the royal court’. Gungnyeo was used to generally describe all types of women who were working inside the palace, serving the royalties living in the royal quarters. Gungnyeo consisted of the high ranking court ladies as well as the ordinary court ladies without any rank who did most of the labour work known as nain (나인) and the other types of working ladies who were not included in the ranks such as bija (비자), musuri (무수리), gaksimi (각심이), bangja (방자), and uinyeo (의녀).

Generally, the court ladies were chosen among the young girls of the commoners or sangmin and the private female slaves of the governing class or sadaebu. However, the commoners were against this practice of sending their daughters to work in the palace at an early age and chose to marry off the daughters at a very young age to avoid being picked as the court ladies. Hence, the candidates for the court ladies were later picked among the private slaves as well as the government slaves, together with the daughters of the aristocrats’ concubines who were once courtesans or slaves. The appointment process was different for court ladies associated with the inner quarters for the king and queen since they were closely working with the royalties and for this reason, the nain for the inner quarters were recruited by the high ranked court ladies themselves through recommendations and connections.

The nain for the departments with specific skills such as sewing and embroidery were from the middle class or jungin while the ordinary nain were mostly commoners. The lower class gungnyeo came from the cheonmin class or the vulgar commoners. The age of the trainee court ladies were in between 4 to 6 years old when they first entered the palace but there were some trainees who entered when they were older, with the maximum age was 13 years old. These young trainees, who were also called saenggaksi (생각시), received proper education to become a gungnyeo, for instance education on the court language and palace etiquette. They would be elevated from the saenggaksi level to a nain when they passed a coming of age ceremony and later, when they had served the court for more than 15 years, they would eventually be promoted to higher ranks, with the top rank that could be achieved by a court lady being sanggung.

The nain were divided into seven main departments inside the palace: jimil (지밀), chimbang (침방), subang (수방), sesugan (세수간), saenggwabang (생과방), sojubang (소주방), and sedapbang (세답방). Jimil nain were the closest servants who waited and served the king and the queen, plus protecting them from any harm. These ladies entered the palace as early as the age of four in order for them to be trained properly. Chimbang nain were the tailors or seamstresses who made royal clothes and accessories for the royal families while subang nain were the ladies responsible for embroidery, be it for the royal clothing or the palace decorations. Sesugan was the department attending the king and queen’s bath, cleaning, and other necessities such as toilets and the place to spit. Saenggwabang was where preparation of the desserts and snacks took place, including fresh fruits, cooked fruits, baked goods, tea, fruit punches and porridge. Sojubang nain were further divided into two smaller departments: inner sojubang or naesojubang for daily meal preparations and outer sojubang or oesojubang for preparing food for banquets with the help of daeryeong suksu, a special chef for banquets from outside the palace.

Chimbang nain as depicted in the drama Jang Ok Jung, Live in Love.

Chimbang nain as depicted in the drama Jang Ok Jung, Live in Love.

Three other departments for the nain were twiseongan (퇴선간), bogicheo (복이처), and deungchokbang (등촉방). Twiseongan nain specialized in food arrangement while bochigeo was the department responsible for making fires and maintaining the heat for the quarters. Deungchokbang was for lighting candles and lanterns in the palace. The court ladies working as jimil nain were more influential compared to other nain and chimbang nain, together with subang nain, were the next in line in terms of power.

The ranks attainable for the court ladies were:

- 5th senior rank – Sanggung (상궁, 尙宮) & Sangui (상의, 尙儀)

- 5th junior rank – Sangbok (상복, 尙服) & Sangsik (상식, 尙食)

- 6th senior rank – Sangchim (상침, 尙寢) & Sanggong (상공, 尙功)

- 6th junior rank – Sanjeong (상정, 尙正) & Sanggi (상기, 尙記)

- 7th senior rank – Jeonbin (전빈, 典賓) , Jeonui (전의, 典衣) & Jeonseon (전선, 典膳)

- 7th junior rank – Jeonseol (전설, 典設), Jeonje (전제, 典製) & Jeoneon (전언, 典言)

- 8th senior rank – Jeonchan (전찬, 典贊), Jeonsik (전식, 典飾) & Jeonyak (전약, 典藥)

- 8th junior rank – Jeondeung (전등, 典燈), Jeonchae (전채, 典采) & Jeonjeong (전정, 典正)

- 9th senior rank – Jugung (주궁, 奏宮), Jusang (주상, 奏商) & Jugak (주각, 奏角)

- 9th senior rank – Jubyeonjing (주변징, 奏變徵), Jujing (주징, 奏徵), Juwoo (주우,奏羽) & Jubyeongung (주변궁, 奏變宮)

Sanggung was the highest rank for the court ladies and there were two conditions for a court lady to be appointed as a sanggung: one was through advancement after years of serving in the palace and the other one through special appointment by the queen when she slept with the king. The special sanggung had a higher status compared to the ordinary sanggung since she was the woman favoured by the king, but she’s not yet a royal concubine. The ordinary sanggung acted as supervisors to the other court ladies but they were directly held the responsibility of sanggi and jeoneon.

Lady Bong and Lady Hong in the drama Dong Yi are both of the rank sanggung.

Lady Bong and Lady Hong in the drama Dong Yi are both of the rank sanggung.

There were several types of sanggung according to their tasks and their influence depended greatly on who they were serving at that time, for instance the sanggung serving the king was more powerful than those serving the crown prince. The types are:

- Jejo sanggung (제조상궁): Also known as keunbang sanggung (큰방상궁). They were the top sanggung who supervise the rest of the court ladies excluding the royal concubines and seungeun sanggung. They were powerful among the court ladies since they were serving directly under the Queen and the Queen Dowager.

- Bujejo sanggung (부제조상궁): Also known as araetgo sanggung (아랫고상궁), these sanggung were responsible for managing the properties in the safe kept at the inner quarters, including the King’s precious jewels and bolts of silk.

- Jimil sanggung (지밀상궁): Also known as daeryeong sanggung (대령상궁). They were responsible for attending to the king, the queen, the queen dowager, and the royal concubines and received direct orders from the person they served as they were regarded as their lords’ hands and feet.

- Bomo sanggung (보모상궁): They could be regarded as royal nannies since they took care of the princes and princesses. They were addressed as aji (아지, 阿之) by the young princes and princesses. If the prince she took care happened to ascend the throne later, a bomo sanngung could be granted the title bongbo buin (봉보부인, 奉保夫人), which was of the first junior rank in oemyeongbu, right below the princesses.

- Sinyeo sanggung (시녀상궁): The sanggung who acted as assistants to jimil sanggung.

- Seungeun sanggung (승은상궁): The sanggung who were favoured by the king. They were originally the ordinary court ladies or nain, either with rank or without rank, who managed to get the king’s attention and shared the bed with him. Unlike the ordinary sanggung who were older, seungeun sanggung were younger and they got the special appointment of becoming a sanggung because of their relationship with the king. They were given the chance to wear special overcoat or dangui (당의) to differentiate them from the ordinary sanggung and they were excluded from the duties of the ordinary sanggung; however, seungeun sanggung might suffer with harassment from other sanggung, especially when the king stopped visiting her. If they were lucky, they would be able to conceive the king’s children and raised to the rank sukwon among the royal concubines.

- Gamchal sanggung (감찰상궁): The sanggung who enforced the rules for the court ladies. Acting as the inspector sanggung, they conducted the punishments for those who broke the rules as well as giving rewards for outstanding gungnyeo. They were feared by the others since they held the power to punish the court ladies.

Sangui‘s job scope was related to etiquette and daily procedures of the royalties’ lives, working mostly in the jimil department. They were also responsible for jeonbin and jeonchan. Sangbok were the court ladies responsible for the embroidery of the royal clothing in subang and supervising jeonui and jeonsik. Sangsik were those who oversaw the preparation of the food and side dishes and supervise both saenggwabang and sojubang while being responsible for saseon and jeonyak. Sangchim were the court ladies managing the king’s clothing and eating while supervising saseol and jeondeung. Sanggong were like the section heads for the lower class working women, and oversaw the work of saje and jeonchae. Sangjeong worked to maintain the discipline of the gungnyeo under the gamchal sanggung through enforcement of code of conduct and punished those who break the rules while Sanggi was the court ladies responsible for maintaining the documents, records, and ledgers in the palace.

Jeonbin acted as the managers for serving ladies entertaining the retainers and/or the king’s guests in national ceremonies such as award giving ceremonies by the kings or royal banquets conducted by the royalties.They were also in charge of the banquets. Jeonui were the ladies associated with the preparation and maintenance of royal clothing and the hair accessories, including the head gears for special occasions. Jeonseon were the people who prepared the food and side dishes while jeonseol did the cleaning and appropriate preparation for special ocassions such as setting the tents. Jeonje were the nain involved with the production of royal clothing in the chimbang, working as seamstresses or tailors. Jeoneon were responsible for spreading the information to the citizens and relaying messages from outside the palace to the king. Jeonchan worked under jeonbin as the serving ladies in national ceremonies. They were like attendants and waitresses, entertaining the guest who were present during the ceremonies. Jeonsik were the court ladies who attended the royalties with their hair washing, combing, and make ups.

Jeonyak worked closely with the royal infirmary or naeuiwon (내의원), including thepreparation of tonics and concoctions according to the prescriptions made by the royal physicians. Jeondeung worked under deungchokbang department, responsible for making lights, lanterns, and candles. Jeonchae were the ladies who weaved the silk and linen fabrics for palace use and involved with the dyeing work of the fabrics. Jeonjeong worked as the helpers for the court officers, such as for relaying messages and sending documents between them. The court ladies of the 9th ranks – jugung, jusang, jugak, jubyeonjing, jujing, juwoo, jubyeongung – were all associated with the music in the palace. They were also the musicians responsible for performances in national festivals and ceremonies as well as private parties organized by the royalties.

The court ladies working in Eastern Palace, where the Crown Prince resided, were given separate ranks from the main palace court ladies as follows:

- 6th junior rank – Sukyu (수규, 守閨) & Suchik (수칙,守則)

- 7th junior rank – Jangchan (장찬,掌饌) & Jangjeong (장정, 掌正)

- 8th junior rank – Jangseo (장서,掌書) & Jangbong (장봉,掌縫)

- 9th junior rank – Jangjang (장장,掌藏), Jangsik (장식(掌食) & Jangui (장의,掌醫)

Sukyu had the authority to enforce discipline among the ladies working in the Eastern Palace, and also responsible for maintaining the documents and records there. Suchik were attached to the Eastern Palace but held less power although they’re of the same rank with sukyu. Jangchan were given the task to supervise the preparation of food and maintaining the monetary account of the Eastern Palace. Jangjeong managed the documents and administer the security of the palace. Jangseo managed the books in the palace, probably working like a librarian who kept track of the books. Jangbong were assigned the do the needlework including sewing and cloth making. Jangjang‘s assignment was to manage the properties of the palace while jangsik took care of food, firewood, and kitchen utensils. Jangui would prepare tonics and concoctions for Eastern Palace.

As for other types of working ladies, those who worked as musuri were usually from the lowest class, most of the time coming from slave background. They carried out odd jobs and small errands inside the palace such as drawing water and distributing firewood for the quarters inside the palace. Gaksimi referred to the maidservants who did the chores and worked as private seamstresses, housemaid, or kitchen maids for the sanggung. They were also known as bija or bangja. Their salaries were paid by the government, unlike another type of helpers known as sonnim (손님).

Sonnim literally means guests and the word was used as a courtesy title to refer to the helpers brought into the palace to work at the royal concubines’ quarters. They were paid by the royal concubines through the concubines’ own expenses since they were most of the time related to the concubines’ family. They didn’t stay inside the palace, thus the term came into usage as they were people from outside, coming into the palace as ‘guests’.

Uinyeo, or medicine women, were mostly associated with the royal infirmary or naeuiwon and the public clinics, hyeminseo (혜민서). They were chosen among the lower class women, mostly public female slaves, to learn and practice simple medicine skills while running errands for the physicians at the clinics, plus acting as midwives. The uinyeo gave simple treatments to the female royalties when the male doctors couldn’t do so due to the restriction of the Confucianism practiced during Joseon Dynasty. Besides equipping themselves with the medical skills, they were also required to be educated in general education, thus they were taught to read various books such as the Thousand Character Classics and also the Confucian books such as Analects of Conficius to promote virtuous character among them as they dealt with the lives of human beings. Hence, uinyeo was actually a profession which allowed one to get the education which was very limited to women at that time. If an uinyeo was lucky, she could even get promoted to commoner’s class when she managed to cure women of the royal family or the prestigious yangban.

An uinyeo in the drama Mandate of Heaven, Hong Da-in was seen conducting an autopsy for a female murder case victim.

An uinyeo in the drama Mandate of Heaven, Hong Da-in was seen conducting an autopsy for a female murder case victim.

There were three types of medicine women: naeui (내의) the active doctors at the royal infirmary, kanbyeongui (간병의) the practical doctors who were studying and giving treatments at the same time, and chohakui (초학의) the new medicine women. The female physicians were also working outside the palace, lending their medicine skills for crime investigation related to women. During Yeonsangun’s reign, these women also served as uigi (의기) or medical entertainers, where they attended the officials’ parties and entertained the guests along with the gisaeng. Acting out the role as both nurse and courtesan, this earned them the nickname yakbang gisaeng (약방 기생), which can be translated as medicine room entertainers.

Oemyeongbu

If naemyeongbu consisted of the women who were the king’s women and the future king’s women, oemyeongbu was the division for other women in the palace that were not the king and the future king’s women. The division was made of the women staying inside the palace such as princesses, the queens dowager and the children of the crown prince and the women staying outside the palace, such as the wives of other royalties and the wives of the government officials.

Among the female relatives of the royal family, princess /gongju (공주, 公主), the daughter of the king with his queen consort, and Princess /ongju (옹주, 翁主), the daughter of the king with his concubine, were at the top among the women in oemyeongbu. They had no rank as they were at the top, same as the queen in naemyeongbu, but the queen was still the supervisor for oemyeongbu. The ranks for the women of the royal family or jongchin (종친,宗親) were:

| RANK | SENIOR | JUNIOR |

| 1st |

|

|

| 2nd |

|

|

| 3rd | Shinbuin (신부인, 愼夫人) |

|

| 4th | Hyein (혜인, 惠人) | Hyein |

| 5th | Onin (온인, 溫人) | Onin |

| 6th | Sonin (순인, 順人) | – |

Hyunbuin, shinbui, hyein, onin, and sonin were the titles given to the royal relatives, either the wives of the relatives or the direct female relatives, but I haven’t found any reliable sources that described their exact relationship with the kings or with the main royal family.

As for the wives of the government officials or munmugwan (문무관), their ranks in oemyeongbu followed the ranks of their husbands. The titles were given collectively to the wives of the officials according to their husbands’ ranks, for instance jeongkyeong buin (정경부인), which was given to the wives of the officials of 1st Senior Rank. There were 18 ranks altogether in the government positions of Joseon Dynasty and the same ranks were applied for the wives’ ranks in oemyeongbu.

| RANK | Senior | Junior |

| 1st | Jeongkyeong buin (정경부인, 貞敬夫人) | Jeongkyeong buin |

| 2nd | Jeongbuin (정부인, 貞夫人) | Jeongbuin |

| 3rd | Sukbuin, (숙부인, 淑夫人); Suk-in (숙인, 淑人)* |

Suk-in |

| 4th | Yeongin (영인, 伶人) | Yeongin |

| 5th | Gongin (공인, 恭人) | Gongin |

| 6th | Uiin (의인, 宜人) | Uiin |

| 7th | Anin (안인, 安人) | Anin |

| 8th | Danin (단인, 端人) | Danin |

| 9th | Yuin (유인, 孺人) | Yuin |

*Note: Suk-in, although held the same rank, had less power compared to sukbuin.

Yangban

The women of the yangban class didn’t attain the status because of their own accord. These noblewomen inherited the social class of their ancestors and their spouses. The yangban women were the official wives and the legitimate daughters of the yangban men, most of the time being the government officials who worked in the court and also took part in managing the nation. However, their roles didn’t stop there as these yangban women, especially the wives of yangban, held immense power in her household. Just like a queen in the palace, the wife of a yangban family held the responsibility to manage the household, including supervising the servants and slaves. The wife was respected by them since she’s the owner of the inner quarters or anbang (안방), where most of the house chores took place.

As the mistress of the house, the wife was granted the power to punish the slaves when they made mistakes and she would administer the chores given to them, especially those related to the inner quarters such as cooking, washing clothes, ironing, and sewing. Although the head of the family was the husband, the wife was given the authority to manage the household’s storage room and the family’s account, not forgetting overseeing the children’s education and taking care of the in-laws. The wife was also responsible for the ancestral rites and became the representative of the house, as in being a good host to the guests.

Yeon-woo practicing embroidery with her mother in The Moon that Embraces the Sun.

Yeon-woo practicing embroidery with her mother in The Moon that Embraces the Sun.

Yangban women were not allowed going out during daytime. They were only permitted to make any trip outside when the men would be inside, covering their faces with jangot and traveled using palanquins. Only in several circumstances, such as bidding goodbye to the relatives, the women would be allowed to go outside during daytime. The unmarried daughters were not encouraged to leave the inner quarters except for important events, let alone going out of the house. Women at that time were not allowed to engage in outdoor activities, such as riding horses, attending parties, and taking parts in games. These activities were forbidden by law and failure to abide it would entitle them to punishment.

The daughters of a yangban family were raised in the inner quarters. Just like the mistress of the house, the daughters were educated to be chaste. The unmarried ladies would be learning simple texts and Hangul that would be enough for them to carry out their duties as wives and mothers in the future. In addition, they would be getting lessons centered on the expected behaviour of women and domestic skills such as cooking, weaving, embroidery, and stitch work. The focus of the young girls’ education was to inspire them towards becoming a typical woman instead of deviating from the norm. Variation would not be tolerated and they were expected to embrace the conventional image of a noble woman at that time. Women’s Instruction or Naehun, penned by Seongjong’s mother Queen Sohye (widely known as Queen Insu), listed out the basic features of an ideal woman: moral conduct, proper speech, proper appearance, and womanly tasks. According to the book, a woman did not need to be of amazing talents, confident, beautiful, or intelligent, for she was only required to become someone who was quiet, restrained, proper and capable of handling domestic tasks. The role of woman was defined as a supporter for her in-laws, husband, and sons.

When it was the time to get married, these ladies would have their husbands chosen by their parents and they would move in with their spouses’ families later. A married woman needed to serve her parents-in-law, her husband, and her children with utmost obedience and care. She would be integrated into her husband’s family, thus she could not hold the same degree of affection as her male siblings for her natal family. Because of this reason, a married woman would be allowed to wear the mourning clothes and conduct the mourning for her natal family only for a short period of time. She had no right to inherit the family’s assets since she did not carry out any responsibilities towards her family. Mourning, ancestral rites, and managing the family were done by the sons or the first sons to be exact, so the sons had more rights to get the inheritance, plus they were the people who continue the family line through the birth of sons to carry the family name. There were exceptions to the inheritance issue, especially when one’s family had no immediate male relatives. In this case, the married woman would get the inheritance but towards the later Joseon Dynasty, the document would state her husband as the one who officially inherited the share, thus the woman would not have any control over the inheritance.

As the principal wife, a yangban woman was expected to bear a son to continue her husband’s family line. Failure to do so could lead to divorce but this was a rare occasion since the husband was allowed to take in concubines to produce the male heir for the family. The sons from the aristocrats’ relationship with women of the commoner’s class were called seoja (서자), while the sons of the concubines among cheonmin would be called eolja (얼자).Talking about divorce during Joseon Dynasty, a husband could only divorce his wife when she committed on of the seven sins or chilgeojiak (칠거지악, 七去 之惡). The seven sins were: disobeying the in-laws, inability to bear a son, having an affair, harbouring extreme jealousy, contracting a disease, talking rudely, and stealing. Jealousy, rude behavior, and serious disease were considered minor compared to the other four. However, the wife couldn’t be sent away from her husband’s home when one of these three exceptions or sambulgeo ( 삼불거, 三不去) occurred: she had completed the three-year mourning period for the dead in-laws, she had contributed towards the family’s status upgrade when she was married, and she had nowhere to go after the divorce. The power to grant the divorce was in the hands of the state and the husband, while the women had no power to decide on it.

A married woman was expected to be chaste and loyal to her husband even after his death and remarriage was not encouraged. At one point, a man could be stripped off his government position if he happened to marry a widow while the widow would be sentenced to death. The penalty was more severe for the women because a lady was educated to be filial to her parents and her in-laws, loyal to her husband, and obey her son when her husband died. This chastity and loyalty to the husbands were important to the point that the government gave awards and recognitions to those who preserved their chastity and led an exemplary life by being loyal to their husbands. A widow whose husband died before her would be applauded if she stayed single until her death and it would be even more honourable for her if she followed after her husband by committing suicide or starving herself to death.

One of the ‘victims’ of the virtuous woman award: Seo Yi-hwa. She was featured in the drama You from the Stars as a young lady whose husband died before her wedding ceremony. In order for their family to get the virtuous woman award for her, Yi-hwa’s mother-in-law tried to murder her and stage it as a suicide to prove the young lady’s loyalty to her spouse.

One of the ‘victims’ of the virtuous woman award: Seo Yi-hwa. She was featured in the drama You from the Stars as a young lady whose husband died before her wedding ceremony. In order for their family to get the virtuous woman award for her, Yi-hwa’s mother-in-law tried to murder her and stage it as a suicide to prove the young lady’s loyalty to her spouse.

The virtuous woman award or yeolnyeo (열녀) was intended to set a good example but the situation got worse in the late Joseon Dynasty, where the widows would kill themselves after their spouses’ deaths to be acknowledged as virtuous women, a title that would bring great honour to both family sides. It reached a point where a woman betrothed to a man would commit suicide if her husband-to-be happened to die before the wedding took place. This was because of chastity, which was considered the most important thing to a woman. Chastity was a big issue during the wars that the women would kill themselves when they are threatened to give up their honour. Those who returned alive were frowned upon in the society and had to live the rest of their lives being humiliated. They suffered harsh treatment not only from the public, but from their own family members as well. With the same reason, adulterous women could end up being sentenced to death in worst case scenario and those who did not would have their sons prohibited from taking the civil service examination, which would put a hindrance for the children to advance in their future lives.

Women of the Joseon Dynasty (Part 2)

Source | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

Thank you so much!!

It’s okay, I actually like reading long replies😀

Indeed, Sukjong’s queens and concubines are very famous figures and their stories are so interesting and intriguing. I think I will never get bored watching different period/historical dramas about Sukjong and his consorts😊.

In fact, I’m watching a relatively old historical drama called ”Jang Hui-bin (2002)” and I found myself hooked to it! I have always wanted to watch it but I couldn’t find it anywhere….until a channel uploaded the 1st episode on youtube with english subtitles and the other 22 episodes are uploaded in dailymotion.. (there are a total of 100 episodes😂)

Hi, thank you for such informative research. In dramas they often show yanban girls at the marketplace looking at at hair accessories etc. Is that something they would have been able to do in reality since they weren’t allowed to leave their houses?

You’re welcome! And thank you for the question too.

In reality, women would not be able to share a space with men outside her family circle. Even in a family setting, women were ‘confined’ to the inner compound of the house. In the case of women going to the marketplace, early Joseon dynasty saw the transition from more lenient Goryeo to the rigid Confucian nation of Joseon, hence there were more freedom for women to move around. But then, they were required to cover their faces using veils and coats. It got worse as the dynasty progressed, since Neo-Confucianism rooted itself in every aspect of Joseon people’s lives. Women were prohibited from leaving their quarters and the inner compounds; if they wanted to buy accessories and stuff, the peddlers would be visiting these noble women’s houses.

Hope this answered your question!

Thanks so much for your reply

I was wondering how the daily life of a Joseon Princess was. What were they doing every day after they got married? Did they maintain their royal status and enjoy the same privileges as they did before their marriage? Also were they able to handle political matters or act as the king’s advisor?

Anionggaseyo

It would be a kind gesture of yours if you tell me about the view koreans have on hee bin mama jang ok jung? Do they consider hee bin mama as good lady or bad villian

Hello~

The traditional view on Heebin (which is evident through the dramatization of the figure) was that of a villain, but there is the modern interpretation by historians (which in turn affect public opinion as well) that sees her as a victim of the power play between King Sukjong himself and the political factions, which included Queen Inhyeon and Choi Sukbin.

Hi again, I just rewatched Yi san (it’s honestly such a nice one to re-watch) and I just realized they call Yi San’s mother Hyekyung-gung (before and after Yi San becomes the king). Why is that? She was married to Crown Prince Sado, so wouldn’t she be called sejabin? Why did they change her title? And why doesn’t her title change after her son becomes king?

Hello Zoe!

Just like how the King and the Queen did not have any title when they were still alive and only referred to using the plain titles and styles His Majesty the King and Her Highness the Queen, the Crown Prince and the Crown Princess of Joseon would only receive titles when they passed away or if the husband died first before the wife. In the case of Lady Hyegyeong, here’s a list Lady Hyegyeong’s status and titles after Crown Prince Sado’s death:-

– as Crown Prince Sado’s widow: Crown Princess Hye (혜빈) bestowed in 1762

– as King Jeongjo’s birth mother: Lady Hyegyeong (혜경궁) bestowed in 1776

– as consort of posthumous king Jangjo (Sado): Queen Heongyeong (헌경왕후) bestowed posthumously in 1899

Although Lady Hyegyeong was Jeongjo’s mother, the situation was a bit complicated for Jeongjo because of his birth father, Crown Prince Sado, who was put to death by his grandfather, Yeongjo. In order to protect Jeongjo from further criticism by the courtiers, Yeongjo made him the adopted child of Yeongjo’s eldest child Crown Prince Hyojang, who died in childhood. So, when Jeongjo went to sit on the throne after Yeongjo’s death, his legitimacy was linked to Hyojang, instead of being Sado’s child. Thus, despite having her son becoming the king, Jeongjo was not considered Lady Hyegyeong’s son by law. The title used for her was bestowed upon her for being the king’s birth mother. The title is gungho (궁호), used as a courtesy title for women in the palace according to their residence/ place of stay.

Crown Prince Hyojang was posthumously honoured as Jinjong, while Jeongjo only gave a posthumous title Crown Prince Jangheon to his own father while expressing the wish for his father’s matter not to be mentioned again. Sado was only made the posthumous king by his descendant Gojong, with the same intention of linking his legitimacy to his ancestor, thus giving the title Queen Heongyeong posthumously to Lady Hyegyeong long after her death.

Oh, so Gung was the title for her because she was his birth mother though he was adopted or because it is her place of residence? Sorry, I’m a bit confused 😅

The title gungho (궁호) was actually a courtesy title bestowed upon the females residing in the palace according to their place of residence. It was given to the King’s concubines who either had their sons becoming the King or those who entered the harem through selection in late Joseon. Back then, in the only people who were permitted to reside in the palace were the Dowager (late King’s wife), the Queen, the King’s concubines, young Princesses, Crown Princess, Crown Prince’s concubines, Grand Heir’s consorts and concubines, and the palace maids. As for Lady Hyegyeong, although the title was used for King’s concubines prior to her, the title was given to her because she was the King’s birth mother. There was no exact title system reserved for her position as the King’s birth mother who was legally married to her spouse, hence adaptation of the title of Gung. Her title could be translated as Lady Hong of the Hyegyeong Palace (Hyegyeonggung Hong-ssi).

Sorry for the confusing explanation earlier 😅

Thank you! This clears things up so well!!

Great article. Makes me very grateful to be born today and not few hundred years ago in Korea. Thank you so much for the article!

May I have a question? Resently I became fond of Korean historical dramas and what has surprised me that in most of the movies/series the members of noble and royal families (and even women) know to read and write. Is it complete fiction or did people of Goreo or Joseon times really learn to read and write?

Thank you.

Hi Jana! Thanks for visiting and leaving a comment.

As for your question, yes, people of noble families in both dynasties of Goryeo and Joseon were literate, but the level of literacy varied between genders: men would be very well-versed in Hanja/Chinese characters due to the nature of the texts and documents written in it, while women would have different levels of literacy: some could read and write only in Hanja, while some could only read/write basic Hanja while knowing the Hangul, especially during Joseon after the promulgation of the letters. The nobles were known to fancy literature and poetry, and several historical figures who were known to be excellent calligraphers were women of noble and royal status. So, it is not a complete fiction 🙂