We heard a lot of things about Joseon Kings, Queens, Crown Princes, Crown Princesses, and the Princes, since they are heavily featured in historical dramas as important characters. Unlike Disney Princesses, Joseon Princesses are seldom included in the modern retelling of history through sageuk. Hence, it is normal to feel intrigued about these princesses of the past: how did they live, and how did their marriage differ from that of ordinary Joseon women (including the Mother of the Nation, the Queen) in the society which upheld strong Neo-Confucianism beliefs? Although their lives were mostly obscure, modern studies have been made to discover details of these royal daughters’ lives told through the official records and personal writings.

Despite not being directly involved in the nation politics and had no say in policy making, a Joseon Princess held a special place in the royal family as the daughter of the man holding the most revered position of a ruler; she was the apple of her royal father’s eyes, and in some way, became a subject of discord between the king and his retinues.

When a royal daughter was born in the Royal House of Yi, her day, date, and time of birth would be kept to be recorded in the Royal Genealogical Records of Joseon Royal Family in the legitimate and illegitimate daughters subdivision Record of Other Royal Clan or Yuburok 유부록(類附錄). However, the earlier genealogical records of Joseon Dynasty were destroyed during the wars and invasions in mid-Joseon, hence there were missing records pertaining to the details of earlier princesses. One of the few royal records which survived until today is the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty/Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty 조선왕조실록(朝鮮王朝實錄), but there were times where the birth of a Princess was not recorded in the Annals. Sometimes, the mention of the Princess’ birth would be made only when there were special occasions such as the gifts from the ministers or the banquets held in conjunction with the birth.

When a royal baby was born, there was a unique practice embraced by the royal family of Joseon called Antae 안태(安胎) or burial of the placenta. It was believed that the placenta was the royal child’s companion in the mother’s womb, hence it ought to receive proper treatment to ensure the child’s long and healthy life. The practice was considered important by the royal family of Joseon and became a tradition since Goryeo Dynasty. Around 3 to 7 days after birth, the placenta would be cleaned in complicated steps of 100(!) washes with water and once with wine. Then, it was wrapped in a white cloth before stored in a placenta jar called tae-hangari 태항아리 together with a piece of coin used at that time, dongjeon 동전. The placenta jar was then placed in a bigger outer placenta jar, bakkat tae-hangari 바깥 태항아리. The jar was to be stored in the delivery room for 3 to 5 months while the decision for a suitable spot was to be made for placenta burial. An auspicious spot would be chosen, soon to be known as taesil 태실 or placenta chamber and a ceremony was held for the ritual. When a royal child became the king, the spot would have its status elevated befitting the owner’s noble status. The royal placenta chambers of Joseon were scattered around the peninsula and it was cumbersome to keep up with the maintenance of the faraway chambers, hence King Yeongjo declared that the practice of placenta burial to be carried out in the palace’s garden to save costs.

Although many of the faraway spots went missing due to looting, demolishment, and lack of care because of their remote places, King Sejong had a brilliant idea of putting his children’s placenta jars in one spot called Taebong (which literally translates into Placenta Peak) and the royal placenta chamber is still intact until today in Seongju. Various places throughout Korea also bear the prefix Tae- to their names, alluding to their once famed status of being the auspicious spots for royal placenta chambers, like Taejangdong in Wonju City, Gyeonggido Province, which was the site of Princess Bokran/Jeongsun’s (정순옹주) placenta chamber. She was the daughter of King Seongjong.

Joseon had a high infant mortality rate which contributed to the low average life span of 30-35 years old among the citizens, and royal babies were not excluded from this fate. The harsh weather and also a lack of protection from diseases contributed to this, hence those babies born in scorching hot summer and freezing cold winter would have a hard time surviving their early years. Even when they grew up, there were many who did not pass the teenage phase because of diseases topped with lacking an immune system. They were living in a controlled environment and did not develop decent antibodies, so when they contracted infectious diseases like measles, they would easily succumb to death. Thus, there were royal sons and daughters who passed away early on, being only a few months, years, and even teens. Their deaths would be recorded in the Annals in the event of the King informing the Ministry of Rites for the burial procedures and rituals. King Sejong’s eldest daughter, Princess Jeongso (정소공주), passed away when she was only 13, thus causing him to grieve deeply for his young daughter. It was recorded that the high-ranked ministers at that time all paid respects during her mourning ritual.

There is no doubt that a royal baby would be welcomed with great expectation and anticipation from everyone in the family. If the child turned out to be the eldest son, then the expectation would sore even higher from the day of his birth; however, a daughter would be spared from the great expectation, unlike her oldest male sibling that would have all eyes on him as the potential successor to the throne. Upon birth, a royal daughter would naturally be the object of affection of her parents, with no strings attached. She seemed to be fated for a pampered early life, except in some unique cases. Her mother the queen (or the royal concubine) would breastfeed her right after birth, but this task would soon be passed to a wet nurse or yumo 유모 in order to give way to the mother’s recovery. The royal daughter would be placed under the care of a court matron acting as the child’s nanny, known as bomo sanggung 보모 상궁.

The royal child would not straight away be crowned with her official title yet and written simply as royal daughter or wangnyeo 왕녀(王女) in the official records; instead, she would either be given a childhood name or a-myeong 아명, which often escaped the official records aka the Annals, or simply referred to as Her Young Highness, agissi 아기씨 by her maids. This is different from the style agassi, assi or aegissi (which translates to Young Lady), since agissi was reserved for young royal children of regardless of their genders. The style of agissi would remain in use even after the royal daughter receives her official title and then replaced with the style jaga 자가 when she got married. I have to say that historical dramas seldom use the jaga style but chose the wrong style of mama 마마, which was actually reserved only for Queens consort and dowager. The same thing happens with the style for Grand Prince and Prince: they should be addressed with the style daegam 대감 instead of mama, which was only applicable for the Crown Prince.

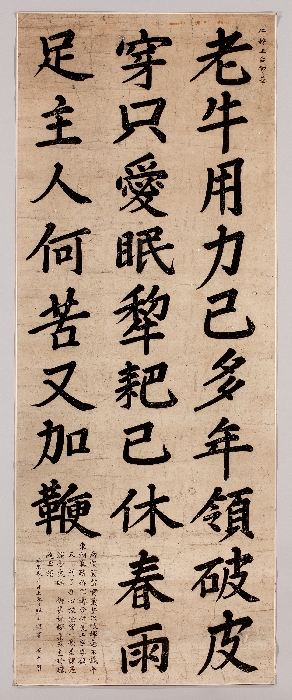

The calligraphy work of Queen Inmok, the second Queen consort of King Seonjo and also mother or Princess Jeongmyeong. Notice how Princess Jeongmyeong’s calligraphy bore strong resemblance to her mother’s. ©National Museum of Korea.

Apart from the wet nurse and the nanny court matron, the royal daughter would have her own entourage of court ladies and palace maids at her service. They would be the people taking care of and staying beside her. Although her male siblings would be enrolled in a proper learning session for their education, the princess would not have the chance to do so. Her early education would be done by her parents when she spends time with them, and it is interesting to see how Joseon Princesses’ handwriting and calligraphy styles were strongly influenced by their royal mothers and fathers. Despite the lack of documentation regarding the education pathway for Joseon Princess, it can be understood that they were also taught the basic skills expected from women of their times. Just like the young noble ladies of the aristocrats, they would be taught how to read and write, as well as sewing, embroidery, weaving, and cooking, not forgetting the etiquette befitting a royal lady. The texts used for the education of a princess were possibly similar to those used by the noblewomen, including Thousand Character Classic or Cheonjamun 천자문(千字文), Elementary Learning or Sohak 소학(小學), Biography of Exemplary/Virtuous Women or Yeollyeojeon 열녀전(列女傳), and later the comprehensive Instructions for Women or Naehun 내훈(內訓), compiled by Queen Sohye (or the title she was more widely known, Queen Dowager Insu), mother of King Seongjong.

When a royal daughter reached the age around 8 to 10 years old, the time had arrived for her to receive an official title that would be used to refer to her for the rest of her life, except in certain circumstances which required the title to be changed. Here is one interesting thing about Joseon Princesses: there were different types of titles for them depending on their birth status, despite the single transliteration of those titles into the English “princess”. The King’s daughter with the Queen would be crowned as Gongju 공주(公主), while the concubine’s daughter would receive the title Ongju 옹주(翁主). The Crown Prince’s daughter with the Crown Princess would be referred to as Gunju 군주(郡主), while his daughter with a concubine would be Hyeonju 현주(縣主). Those with the titles of Gunju and Hyeonju would be upgraded to Gongju and Ongju respectively once their father the Crown Prince became the King, except for those whose father neither ended up as a ruling or a posthumous King like the daughters of Grand Prince Yangnyeong (King Taejong’s Crown Prince who was replaced by his brother Grand Prince Chunnyeong, later King Sejong) and Crown Prince Sohyeon (King Injo’s eldest son who suddenly died after a strained relationship with his father). The personal titles of the Princesses often shared identical characters with their female siblings and bore feminine meanings to them.

| Princess Title | Rank |

|---|---|

| Gongju 공주(公主) | no rank |

| Ongju 옹주(翁主) | no rank |

| Gunju 군주(郡主) | Sr. 2 |

| Hyeonju 현주(縣主) | Sr. 3 |

[for more information on the detailed ranks in Naemyeongbu and Oemyeongbu, check out the post Women of the Joseon Dynasty (Part 1).]

Unlike the general assumption that the Princess was part of the Inner Court since she was born as part of the royal family, all princesses were grouped as women of the Outer Court or Oemyeongbu 외명부(外命婦) instead of the women of the Inner Court or Naemyeongbu 내명부(內命婦), and they would partake in activities inside the palace like weddings, banquets, and special occasions like New Year celebrations. Despite spending their early lives in the inner court, they eventually had to live outside the palace, hence they were classified under the women of the Outer Court. Both Gongju and Ongju were placed on top of the rank in Oemyeongbu and stood on the same level in terms of ranks, but there was still the distinction between the two ranks of Princess. This is due to their birth mother and their legitimacy of birth, being either a Queen or a royal concubine’s child. Naturally, Gongju would be treated with more respect compared to Ongju, but there was also the different treatment given towards Ongju. Depending on their mother’s origin, Ongju could be the daughter of a noble class concubine (who mostly came in through selection) or a humble class concubine (who originally worked as a palace maid and received the King’s favour).

In the case of Princess Suknyeong (숙녕옹주), she was the only illegitimate issue of King Hyojong, who had six legitimate daughters with Queen Inseon. Her mother Lady Yi Anbin became King Hyojong’s concubine from his Grand Prince Bongrim days and she even followed him to Qing during his years of becoming a hostage in Shenyang. There was an episode where King Hyojong summoned his children to present them with gifts but left out Princess Suknyeong since he did not want to offend his wife. However, Queen Inseon was very much aware of King Hyojong’s strong love for his children, so she also called for Suknyeong to meet him. Even after she got married, King Hyojong wanted to treat her just like his other children, but his action was stopped by his courtiers due to the rules of the court. Princess Suknyeong married Park Pil-seong; unfortunately, her life was short and she died of measles. Her husband lived a long life until King Yeongjo’s era and received the King’s gift in his later years. As for her mother Lady Yi Anbin, she did not get any title while King Hyojong was alive and stayed as a favoured court lady despite giving birth to the Princess. Perhaps, it was in line with the rule which dictated that the legal mother of all King’s offsprings was to be the Queen. She only received her first and subsequent titles during King Hyeonjong and Sukjong’s reigns, living until the latter’s era.

A Joseon Princess would usually be married off in their teens except in situations like major royal family member’s death, severe drought, or in Princess Jeongmyeong (정명공주)’s case, locked in the Western Palace with her mother Queen Inmok and demoted to the status of Ongju in her teens. The marriage talks would start around the age of 10 to 16, with the target age of their suitors between 11 to 16 years old. The consort of the Princess could be older, younger, or of the same age as her, depending on the situation. The wedding was also known as Haga 하가(下嫁) to symbolize the act of the Princess “marrying down” someone of lower status than her. As for the scale of the ceremony, a Princess’ wedding stood somewhere between the more complicated major royal wedding ceremony or garye, and the standard wedding steps practiced by the noble class.

There was an interesting incident that eventually led to the marriage rites for Joseon Princesses that we know until today. The first step for marriage in Joseon was to make a proposal through a matchmaker and this process was called euihon. King Taejong wanted to find a suitor for his daughter Princess Jeongsin (정신옹주), so he sent a matchmaker named Jihwa to the house of Yi Sok with the intention of asking his son’s hand in marriage. Lo and behold, the proposal was rejected because Princess Jeongsin’s birth mother, Lady Shin Shinbin was a palace maid, and Yi Sok haughtily stated that he would only let his son marry a princess like Princess Jeonghye (정혜옹주), whose mother Lady Kwon Uibin was selected royal concubine from the noble class. This matter reached King Taejong’s ears and of course, he was livid to hear that. He stopped at nothing to make Yi Sok’s life a living hell, from hitting him 100 times with the paddle and demoting his status to a commoner and then a slave, to prohibiting Yi Sok’s son from marrying anyone, turning him into a bachelor for his whole life.

In order to prevent something like that from happening again, it was suggested for a selection process to be arranged for the purpose of choosing the consort of a Princess, also known as Buma Gantaek 부마간택, when the marriage of the youngest legitimate daughter of King Taejong, Princess Jeongseon (정선공주) was being discussed. This first-ever consort selection process was a bit different since King Taejong ordered his royal secretaries to suggest a few men of suitable age who came from the family with a member of fourth or fifth rank or below. After that, the candidates were summoned for an audience with the King himself before the decision was made to choose Nam Hwi as the King’s son-in-law or the Prince consort, Buma 부마(駙馬), also known as Uibin 의빈(儀賓).

[for more information on the detailed Joseon marriage rites and stuff, check out the Wedding & Marriage in Joseon series, Part 1 and Part 2]

The Princess, unlike an ordinary noblewoman who would move in with her in-laws after marriage, would have her own private residence she calls home after the wedding. In more unusual cases, it would be her in-laws who moved in together with her, if the situation called for it. The residence was either built from scratch or bought from a royal relative before undergoing renovation works that would turn it into a place befitting the status of a King’s daughter. The King would usually spend a lot — to the point of splurging — for his beloved daughter who would get married soon, so it was probably nothing in his eyes…but of course, it became a problem in the eyes of his courtiers. There were continuous issues with the extravagant lifestyle led by the Princesses, from the allowance and the wedding expenditure, to the enormous residence and the excessive estate grants presented to the Princess after her wedding. This practice of indulging in luxury among the royal family continued throughout the dynasty until King Yeongjo put a stop to it by keeping royal occasions simple, omitting steps deemed unnecessary even for his own family.

No matter how much a King loved his Princess, there was one thing he could not do as her father during her wedding ceremony: it was to become the master ceremony or Juhon 주혼(主婚), In normal weddings, the father of the bride would hold this responsibility as the key person on the bride’s side. However, a King could not possibly be burdened with such a task, on top of his daily duties as the nation’s ruler; plus, the reason why the King did not partake in the ceremony was in order to begin the marriage ties between the two families on symbolically equal standing with the groom’s family. As such, the palace would not be regarded as the Princess’ natal home in the ceremony.

A male royal relative, usually an older Prince, would be entrusted with the responsibility of becoming the person presiding over the marriage on the bride’s side. As for the natal home placeholder, it would either be the Princess’ future residence outside the palace or the master ceremony’s house if the residence was still under construction. The natal home, referred to as Gongjubang 공주방, would be the place where the rites on the bride’s side would be held, while the Prince consort would stick to his own house as the Bumabang 부마방. Formal proposals and wedding gifts would be exchanged through napchae and nappye rites respectively before the big arrived. The duration of the whole wedding ceremony — from the marriage ban to the selection right until the procession of Princess to her private residence post-wedding — would take months at least, but younger Princesses might take more time after the ceremony before moving out of the palace.

Not all men could dream of becoming the Princess’ consort or the King’s son-in-law. If the requirement to become a Queen consort included the high status of the candidates, it was the other way around for the Prince consort. The preferred candidates were picked among the families of officers rank 4~5 and below. Their families needed not to be too illustrious, and there were several reasons behind it. The King probably wanted to spare his precious daughters from the pressure of powerful in-laws and make their married lives easier. Plus, having in-laws who were too powerful might possess more problems to the throne itself. They might flaunt their ties to the royal family itself wield their influence; combined with their already powerful position prior to the marriage, it might lead to an unbeknownst future. As for the Prince consort himself, having an over-achieving family would not do him any better, as there were more things he could not do in order to become a Princess’ husband.

| Princess Title | Prince Consort Title | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| Gongju 공주(公主) | Uibin 의빈(儀賓), later Wi 위(尉) | Jr. 1 |

| Ongju 옹주(翁主) | Seungbin 승빈(承賓), later Wi 위(尉) | Jr. 2 |

| Gunju 군주(郡主) | Bubin 부빈(副賓), later Buwi 부위(副尉) | Sr. 3 |

| Hyeonju 현주(縣主) | Cheombin 첨빈(僉賓), later Cheomwi 첨위(僉尉) | Jr. 3 |

Upon marriage, the Prince consort would be given a rank with respect to his spouse’s rank, but of course, lower than her. However, the rank was just on the paper instead of a working rank; a Prince consort could not hold office except with special order from the King himself, such as acting as an envoy to Ming/Qing or managing the Office of the Prince Consorts, Uibinbu 의빈부(儀賓府). It could be frustrating for a man of high ambitions to be stuck in a position where he could do literally nothing, hence rather than aiming for the high achievers, the target group would be those young men who were learned enough but not too fixated on or promising with the office. Despite the limited freedom of movement, there were those who aimed to become the Prince consort because of the advantage of forming ties with the powerful and the wealth that would come with it. Perhaps, the Prince consort would view himself as the stepping stone for his father and brothers to bring honour to their family. Nevertheless, his status would always be a dangerous one, being a Princess’ husband and the King’s son-in-law.

Even in the marriage realm, a Princess’ life was different from a normal one. In this case, the Prince consort had to address the Princess accordingly and formally, since she was his superior in rank and status, despite Confucianism’s dictation that the wife should be the one treating the husband as her superior. Perhaps, there were exceptions to a certain extent, just like in this case. Still, the Princess was to be considered a part of her husband’s family once she married the Prince consort; she would be buried in the family’s graveyard and honoured by the descendants of the family. Some had to endure years of lonely life, being abandoned by their own husband in an unhappy marriage, or ended up becoming a widow should their husband died before them.

The life of Princess Hyojeong (효정옹주), daughter of King Jungjong with Lady Yi sukwon, had to be one of the most pitiful among Joseon Princesses. Her birth mother passed away early on and Jungjong felt bad for his daughter who lost her mother at a young age. She married Jo Ui-jeong, but her marriage did not turn out great. Jo took in the Princess’ own maid as his concubine and treated Hyojeong poorly. But then, the Princess continued to protect her husband each time Jungjong wanted to intervene, much to the King’s frustration. Princess Hyojeong’s kind and softhearted nature made her an easy target, and Jo continued his bad habits to the point of letting her sickness after a difficult birth took a turn for the worse before reporting it to the palace. He even stopped the doctor sent by the palace from entering his house, leaving the Princess to die just like that.

As for the Prince consort, there were more don’ts than dos for him in marriage, just like what has been stated before. A Joseon man was allowed to have concubines aside from his legal wife and he was allowed to remarry should his legal wife passed away. This privilege was revoked from Prince consort; he could neither take in any concubine while the Princess was alive nor could he remarry in the case of the Princess passing. He could only take in a concubine after the Princess’ death in place of a new legal wife. The reason behind this prohibition was that the Princess was someone who could not have another person on the same status as hers in the marriage as well as in her in-law’s family, in life or death. Hence, to have another legal wife after the Princess’ death was not permitted for the Prince consort.

There was also a catch with regard to the concubinage: there could be no concubine from the noble class, and should the concubine bore a son from the relationship with the Prince consort, the child would not be considered a legal son of the Prince consort, even if the Princess passed away without having any child. In a normal family setting, if the legal wife could not produce a male offspring, the concubine’s son had a chance to be made the legal son so that he could carry an important responsibility of a family’s male descendant that was jesa or memorial ritual. However, in the case of a passing Princess without any child of her own, the Prince consort would have to adopt a son of his closest relative, for instance, his brother. It was deemed inappropriate for an illegitimate issue that was the concubine’s son to oversee the memorial ritual for the Princess, and it was more appropriate to have someone from the legitimate line to do so. The rule was discussed a few times throughout the dynasty. Despite it being an unwritten rule for the Prince consort in early Joseon, several cases and discussions made it into the Annals, leading to the more stringent regulations around it.

Princess Uisook (의숙공주) was the only daughter of King Sejo. When she was first married to Jeong In-ji’s son Jeong Hyeon-jo, she did not have any title since her father was still Grand Prince Suyang and was simply referred to as Jeong Hyeon-jo’s Wife. When he became the King, she was officially proclaimed as a Princess, so her husband naturally became a Prince consort. The Princess received her personal title Uisook only after her father’s death. She passed away when she was 36 without leaving behind any child, so Jeong decided to marry Lady Yi, daughter of Yi Jing. King Seongjong was the ruler at that time and the matter was discussed; however, he decided that “A noble royal Princess should not have her memorial carried out by a concubine’s son.” Hence, he banned the remarriage of the consort of a Princess with the following rules:

- Remarriage is banned.

- Concubine from the noble class is forbidden.

- Sons of the concubine are not allowed to hold office.

- A son of the closest male relative of the consort should be made the legitimate issue of the Princess and the Prince consort.

As such, Jeong’s new wife did not get acknowledged as his legal wife. The status of their children became an issue for generations. The matter appeared in discussion again during King Jungjong’s era and the King, quoting the common people’s law of allowing men to remarry, granted special permission for Jeong’s family.

King Sukjong decided to tighten the rule when Jeong Jae-ryun, the husband of King Hyojong’s daughter Princess Sukjeong (숙정공주) made a request for remarriage. The Princess died young but they had a son and a daughter together; however, the son died in his teens, thus Jeong asked for King Sukjong’s leniency. But then, King Sukjong refused to budge and reiterated that he should adopt a son from his closest male relative as his heir. The rule continued until the end of Joseon Dynasty, as King Cheoljong’s son-in-law Park Yeong-hyo, only took in concubines after the death of Princess Yeonghye (영혜옹주), despite being married for only 3 months before the Princess’ demise.

There were a number of Princesses and royal daughters who passed away before they were able to get married, hence they were interred in a special graveyard for young unmarried Princes and Princesses. Once a Princess joins her husband’s family, they would be together in life and death, buried on the same plot of grave for her husband’s family. In the case of a passing Princess, the palace should be alerted for arrangements to be made in order to assist with the funeral and mourning rites. The palace would put a hold on court business and assemblies for 3 days, while people below the Princess’ rank in the palace would refrain themselves from eating meat on those 3 days. However, if the Prince consort happened to be the one dying before the Princess, she would have to stay unmarried as a widow until the end of her life. The same practice would be applied if the couple had no child, just like how Princess Hwawan (화완옹주), daughter of King Yeongjo, adopted a male child from her deceased husband’s family side as her own son, Jeong Hu-gyeom.

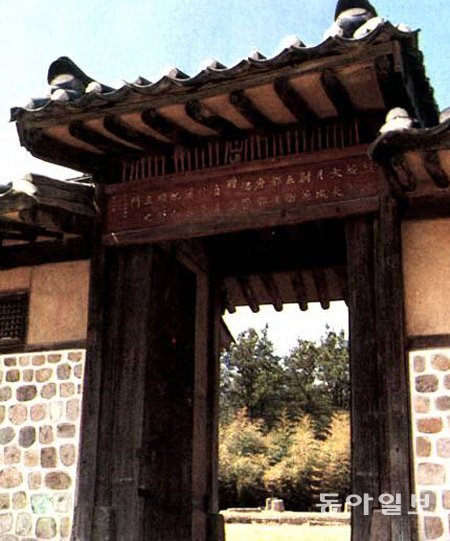

Princess Hwasun’s Red Gate 화순옹주홍문 at the House of Chusa Kim Jeong-hui, her great-grandson through her adopted son. ©DongA Ilbo

Princess Hwasun (화순옹주) was the only member of Joseon royalty who was granted the status of a virtuous woman or yeollyeo 열녀. She was the daughter of King Yeongjo and Lady Yi Jeongbin, and she was the only child among her immediate siblings who survived infancy. She led a lonely early life when her mother died early and King Yeongjo, then Prince Yeoning, was involved in political conflicts prior to his ascension to the throne. She married Kim Han-sin when she was 13 and had a blissful marriage despite not having any child. But then, tragedy struck when Kim passed away when he was 39 years old. Her lonely childhood and the possibility of living a long lonely life by herself all over again probably pushed her into taking the ultimate decision of refusing food and starving herself to follow her husband to the afterlife. She did not stop despite King Yeongjo’s continuous plea to save his beloved daughter. The Princess eventually met her demise 14 days after Kim’s passing. King Yeongjo strongly disapproved of her choice and did not applaud her fidelity, viewing it as being unfilial towards her own father. Perhaps, it was King Yeongjo’s sadness talking, and it was not until King Jeongjo became the King that Princess Hwasun was finally honoured as a virtuous woman. A red virtuous woman gate (hongmun 홍문 or yeollyeomun 열녀문) symbolizing her sacrifice was erected at the Kim family’s household to commemorate her fidelity, and the gate is still standing strong until today in Yesan County, Chungcheongnamdo Province.

Writings by Princess Deokon for the Hangul transcription of Records of the Construction of Jagyeongjeon Hall, Jagyeonjeongi (자경전기), originally written by her father, King Sunjo. ©National Hangeul Museum Korea

Even after the Princesses officially left the palace through the procession called chulhap 출합(出閤), they would still considered a member of the royal family and would required to join important occasions held inside the palace. Princess Deokon (덕온공주), a daughter of King Sunjo, had to attend the first selection process for King Heonjong’s second Queen consort. At that time, she was heavily pregnant but she still made it to the palace. She suddenly had indigestion after a meal and unfortunately passed away because of that. In the case of visitation, some of the Princesses were also visited by the King himself when they fell sick, like what King Myeongjong did to his sister, Princess Uihye (의혜공주). King Danjong was also known to pay frequent visit to his sister, Princess Kyeonghye (경혜공주).

They also received regular stipends in the form of grains twice a year in spring and autumn. In fact, when they first moved out to their private residence from the palace, they had to bring everything to the new house, from the bedding to the smallest grain of rice, so everything had to be prepared accordingly. As for their private residence, although there were standard regulations on the area, some got away with luxurious houses that were comparable to the palace itself. King Myeongjong himself praised Princess Uihye’s garden, saying that it was more magnificent compared to the palace’s own garden. King Yeongjo, on the other hand, was know for his strong love and favoritism towards several of his daughters, and he was recorded to have offered a huge residence to Princess Hwapyeong (화평옹주) when she got married. The residence was said to be of the same level as a royal residence, but the Princess declined her father’s gift.

They might be considered insignificant when they were the King’s daughters, but these Princesses at times lived long enough to see their brothers and even their nephews sitting on the throne. They were respected for their status as the King’s immediate family, but there were cases where the Princesses were either dragged into political struggles or voluntarily getting involved themselves. Princess Jeongmyeong (정명공주), the sole legitimate daughter of King Seonjo, lived through the reigns of six Kings: Seonjo, Gwanghaegun, Injo, Hyojong, Hyeonjong, and Sukjong. Her difficult life in her teens followed through her later life as well, when she was considered a threat by King Injo, whose claim on the throne was initially endorsed by her mother, Queen Inmok. She had to avoid the watchful eyes of the ministers by living quietly and raising her kids. Despite her effort to live in peace, it was not easy at all, considering how her husband Hong Ju-won was from an illustrious family of Pungsan Hong clan and the kings were always being cautious with her. Fortunately, she was treated with respect by King Sukjong as the most senior royal relative at that time. Although her early life was not easy, she was blessed with long life and lots of children who went to be successful in their lives.

One of Princess Jeongmyeong’s descendants would be Lady Hyegyeong, the wife of Crown Prince Sado and the birth mother of King Jeongjo. Lady Hyegyeong had longtime discord with her sister-in-law Princess Hwawan (화완옹주), who was one of Yeongjo’s cherished daughters. It was said that the Princess displayed obsessive behaviour towards King Jeongjo from his Grand Heir days and it continued to the point of her adopted son, Jeong Hu-gyeom, meddling in political affairs. Princess Hwawan was then stripped off her rank as a royalty and exiled, while her son was sentenced to death by poisoning when Jeongjo took over the throne. She was only referred to as Jeong Chi-dal’s Wife or simply Jeong’s Wife in the Annals despite being released from her banishment later in her life, and her humble tomb showed that her crimes were never really pardoned until her death.

Life was never a bed of roses even for the most pampered Princess of Joseon. Their lives, while seemed perfect from the outside, actually had their own ups and downs. They had luxurious and privileged lives full of benefits and riches, and they could get their wrongdoings pardoned as long as it was not related to treason or infidelity. But then a Princess’ position, despite having little to no influence on politics, was actually a perilous place to stand on. The political wind blowing in and out of the royal court might affect a Princess’ life, sometimes way before they were born into this world. She might be implicated if her in-laws happened to be embroiled in political upheaval; worse, when her own father had his authority challenged to the point of facing dethronement. She would also be dragged into the issue involving her mother’s family. Some might not live for a long time under the immense love and care from their royal parents, but a number of them experienced a long journey in their lives, witnessing how the country went through changes under different Kings and how the history was made from a unique point of view. It is unfortunate that we would never get to see things from their perspective, but we get a glimpse into their lives through the historical records and the artifacts they left behind. Perhaps, their lives, with the splendor and beauty combined with the pressure and loneliness, might not be something that can be handled by anyone else but them.

Sources | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

Fascinating! Thank you for compiling this information.

Thank you so much ❤ Glad you liked it!

I am a male Dutch , ( Holland ), Kdrama-fan around for 11 years now.

In the first years I did nightshifts on the Schiphol-airport , in an essential store.

Crew, taxidrivers, travelling people etc.

Watching Kdrana in the eassy hours between 1 and 4.

I am macho to the core ofcourse, so clothes looked nice and colorful in historical dramas.

That was it, the storyline mattered most.

First historical drama was Painter of the Wind with Moon Geun Young.

Low ranking but not for me. Still a favorite.( Very bad translation put a lot of people off )

Moon Geun Young is able to pull you really deep into a drama, if she feels like it.

Many dramas followed, modern and historic in turns.

And the Joseon fashion has become a thing of interest for sure !

Not in the least because of your brilliant reviews and your deep analizing of it,

Like Empress Qi !

Thanks a lot for that !

Our Queen Consort Maxima has earned a lot of interest worldwide because of her choice of dress in everry occasion.

She is a real peoples-queen who visits mom-and-pop shops where-ever she goes, because of her work for the UN.

As easy as visiting Royal gala’ and always shining.

And nowadays I find myself researching photos too , with the lessons I learned through your site.

“”is it a Royal colour, like purple or blue ?” , that sort of questions.

Thanks again and keep up the good work !

Hello! It’s been a while 😀

Thank you so much for you support despite my rare postings…there are so many things to watch, so much things to read and write about!

These days, I’m yearning for sageuk like Painter of the Wind and Hwang Jin Yi…I miss those days, but we’ve been getting less and less of sageuk recently. Hopefully there will be reemergence of slightly heavier sageuk with pretty clothes 🙂

By the way, I read about Queen Consort Maxima and found it interesting that her daughter is the Heir Apparent to the throne. Gonna have to check out her fashion choice too ❤

This is so interesting! It’s almost like you read my mind. I was always curious about princesses, their roles, the hanbok designs because unlike Kings, Queens and Princes, we only get a handful of thorough portrayals of a princess’ life in Sageuks, and even then most of them are fictional.

I remember Princess Sukhwi from Horse Doctor most dearly, and I didn’t watch Hwajung nor Princess’ Man. I was intrigued about Princess Kyunghye(?) even more than Princess Se-ryung…but ended up not watching the drama because of the male lead actor 😅. I loved Princess Deokhye(I think her name is very pretty lol). The Last Princess was a very moving film. But I remember wondering why were there the 4 Circle badges on her dangui, for she was an Ongju not Gongju. Perhaps you can answer for me? Was that deliberate or a mistake from the movie’s costume department?

I remember Princess Hwawan from Yi San and the Princess from that Matchmaker movie(I dont remember the name because I didn’t enjoy it as much as I expected) had danguis just like concubines with no circles on them because they were Ongjus.

However in most dramas I see Ongjus and Gongjus both alike wear those circle badges, but only on front and back with none on shoulders. Sometimes even Gongjus would wear badges with flowers on them not dragons. Princess Sukhwi wore all the 4 badges, but sometimes they had flowers and another time they had dragons. Princess Minhwa from Moon Embracing the Sun only wore 2 flower badges despite being a Gongju.

So, which one is historically accurate? Is this simply a directorial mistake thing, or is the Royal Garment portrayal we usually accept to be “accurate” simply a result of directorial preference and not to be taken seriously? Because even though some dramas seem to have clear-cut rules on their Royal ladies’ clothing, in some photos (That black and white family photo of the last Emperor(?)) the designs seem to be all over the place and probably not rule driven.

Or they used to be neat but became lax towards the end of the dynasty, and we’ll never know and will have to take drama gods’ words because there probably aren’t much info about the Princesses themselves to begin with, let alone lengthy documents of their garments?

Gosh I’m asking so much questions today aren’t I? I’m probably giving you a headache, sorryyy?😅

Suffice to say, thanks again for the intriguing, carefully-put-together, much-needed article.

*Cue Sageuk style bow.

Hello~! Thank you so much for the compliment 😀 I’m so glad people find this one useful deep bow

I never got around watching Horse Doctor because I was doing my internship at the time it was airing, but I still remember how adorable Princess Sukhwi with her cat!

Regarding your question…

The rank badge is commonly referred to as hyungbae 흉배(胸背) (which is also the term used for the square rank badge worn by the officials), but those circular badges used by the royal family are called bo 보(補). The badge with dragon emblem is specifically named yongbo 용보(龍補), with the word ‘yong’ referring to dragon. (credit to: http://folkency.nfm.go.kr/kr/topic/detail/7278)

I just found out that the circle would be called gyeonhwa 견화(肩花) when it is placed on the shoulders. At first, there wasn’t any exact regulation on a Princess’ badge. The Queen’s badge went through changes, from pheasant or jak 작(雀), peacock or jeok 적(翟), and phoenix or bong 봉(鳳), to the dragon emblem seen on the relics of Princess Deokhye’s close family. It was only towards the end of the dynasty (from 18th century onward) that the rest of the female royalty got a detailed regulation, but not for the Princess. Even among the relics belonging to Princess Deokon, the emblem was not attached to the ceremonial topcoat or dangui in her family’s possession.

Thus, I can assume that towards the end of the dynasty/during Korean Empire, dragon emblems were collectively used by the whole royal/imperial family, plus with regard to Korean Empire, their status was one rank higher than Joseon in theory. In the photo you described, both Princess Deokhye was seen with their minor ceremonial robes: the Princess wearing dangui, while Empress Sunjeong (the the Imperial Crown Princess) beside her wore wonsam. Both the Princess and the Imperial Crown Princess used the dragon badge, but in other photos featuring the imperial concubines, they were wearing dragon emblems as well, but on their major ceremonial robes.

Dramas are taking artistic liberties with regard to the badge design, but according to the surviving records, early to mid-Joseon Princesses in dramas shouldn’t adapt the dragon emblem…if we’re talking about logic here 😀 Even the hairpins and the hairstyles in shows have been making headlines when the viewers deemed the style unsuitable for the status of the wearer and the time setting of the story.

I hope that the explanation is not too confusing >.< Don’t feel sorry about the question! I LOVE ❤ receiving questions because I can always learn and read more. Questions and discussions are always encouraged and welcomed over here, as long as they’re healthy ones 😉

No not confusing at all! Thanks a lot for the detailed reply.😁

Makes sense. We see the Yongjams/Bongjams used in the Sukjeong era dramas when it was Sukjeong’s son who banned the Big wigs, so if they take liberties with something major like that no wonder about the inaccuracies in the Princesses’ wardrobe. PD Lee, despite his grand and heartfelt stories of DJG, Dong Yi..etc always seem to disregard fashion accuracy😅. But oh well, I can’t complain because his wardrobes always appease to my inner order-loving OCD tendenecies lol. Different color jeogoris for Cooking and Sewing departments, and different color danguis for senior and junior nurses in DJG? Loved it. Dragon pins for Queen and Queen dowager in Dong Yi, Single Phoenix pin for the humble Choi Sukwon and a different phoenix pin everyday for haughty Jang Huibin? I love those subtle differences, and frankly wigs won’t be that much helpful in that department despite being accurate lol. I think Royal Gambler portrayed this accurately. If I remember correctly Jang Huibin(in the beginning of the drama) was wearing the huge wig, and towards the end(Yeonjo’s reign) his queen and Choi Sukwon were wearing pins.

So according to what you say Princess Sukhwi’s wardrobes had indeed been innacurate, but boy, didn’t I love seeing her sitting in a row with the Queen dowager and the Queen wearing identical clothes…announcing to the whole world that they are obviously the ladies of legitimate Royal line😆.

I thought despite being declared an “Empire” the latter half of the dynasty didn’t have the prosperity of its earlier times? I guess then it makes even more sense to appear as much as “empirical” possible with upgraded wardrobe to convince themselves and the country of their status.🤔

Thanks again! I wish you all the best in these hard times. Here’s to see more and more of your helpful and thorough posts in the future!🍻

Btw is that Park So dam as Princess Hwawan?

It’s a treat for the eyes, really!

Yeah, you got that right with regard to the Empire. Joseon was trying to stand against the growing pressure from various external forces and nations, while Chinese Qing was rapidly deteriorating. Proclaiming it as an Empire was probably one of the last efforts in strengthening the nation, but too many factors led to the Empire being annexed by Japan in the end.

That was her! It was from her short stint as Princess Hwawan in Crimson Blood, KBS Drama Special also starring Kim Dae-myung as the titular Crown Prince Sado.

Oh I also have another random question.

Do you focus mainly on Korean history? I saw you had a post on Ruyi’s Royal love in Palace so I thought to ask whether you have interest in Chinese Royal fashion as well. From what I gathered, they didn’t have the 5S style(😆) of Joseon fashion in their harem, except the “Higher ups get to wear the more elaborate stuff” thing which is granted. But if a high ranking consort decided she doesn’t like fancy and went simple, you won’t be able to recognise her status at the 1st glance, unlike the Joseon harem. I’m a little curious about that. I also find it interesting that Korea followed Chinese fashion for a long time and continued to wear resembling albeit different stuff in the Joseon era, while China adopted a completely new style in Qing Dynasty. And despite being the Empire to the Kingdom of Joseon, the Qing fashion didn’t get imposed upon Joseon and they continued on with the hanboks that share similarities with the hanfus of olden days!

I read quite a few Chinese historical fashion blogs but it was difficult to find detailed ones, and ofc there was none comparing and contrasting the fashion of both countries. (Those detailed and categorised Joseon fashion posts of you are really something else😍) If you have any interest in this topic I would love to read a post from you one day..someday ofc. You’re probably a very busy person. There’s no pressure whatsover.

Cheers~

I’m replying here too so that the comment won’t be too confusing hehehe

5S style got me cackling LOLOLOL

As for now, my focus is mainly on Korean history, with my average Korean language skills playing an important part in this. I started out watching Cdramas and I still find them charming (oh, those harem dramas are unrivaled even by sageuk!), but I only have very basic Mandarin skills, hence the limitation in finding more info about Chinese dynasties clothing. Still, it will be interesting to see how the robes from Ming was incorporated in Goryeo and Joseon’s own style of clothing, and how Joseon managed to maintain the style while Ming’s Han style was replaced by Qing and the Machu clothing. If I ever get to study about this through proper channels, it would be a dream come true! Oh, you’re giving me ideas now 😀

Haha you’re welcome! (If you find a way to do that one day it’d be a dream come true for me too😉)

What a wonderful post!

I’m glad you give us many information about the Princesses of Joseon.

I’m quite interested in those Princesses, so I hope you don’t mind if I ask some questions.

1. In Saimdang’s (2016), the princess had unhappy marriage. She asked the king to null the marriage. The king refused it. But he let her stay in the palace away from her in laws. Was it possible for the Princesses of Joseon to divorce their husbands? How was the process then?

2. How was the marriage arragement for the princess children? Did the princess’s in laws or husband determine the potential suitor? Should the marriage granted permission from the king?

Thank you.

Thank you so much 😀

I totally don’t mind getting questions because it’s another way of learning something new, so feel free to ask away~

To answer your questions:

In Joseon Dynasty, there was something called Seven Sins, which is the list of things that would allow a husband to divorce his wife. While divorce among Joseon Princesses was an extremely rare thing, only the husband had the right to make the decision on having the divorce or not. So, I would say that it would be impossible for the Princesses to divorce their husbands. Even in the case of physical abuse done by the husbands (there were quite a number of this actually), the King would try to intervene and in the worst-case scenario, it would be dealt by sending him to exile or putting him on something akin to a restraining order. I think I have only read one case of Joseon Princess getting a divorce from her husband: Princess Hwishin, daughter of Prince Yeonsangun. She ended up divorced by her husband Gu Mun-gyeong because her father-in-law sided with King Jungjong in the coup to overthrow Yeonsan. She was also reduced to the status of a commoner, but Jungjong made it possible for her to reunite with her husband. However, she lived the rest of her life being an ordinary citizen instead of a royal princess, known simply as Gu Mun-gyeong’s Wife.

The Princess’ children, while being related to the royal family through their mother, were considered the noble class since they followed their father’s status. Hence, their marriage arrangement would follow that of an ordinary family’s steps, involving the Princess’ in-laws. Such marriages did not need permission from the King, but he would be notified of such events especially for those who were close to their maternal grandfather, the King. Although the King did not have any say in their marriages, the Princess’ children did enjoy special treatment and even had their punishments meted out due to the King’s grace, even long after the Princess herself had died.

Oh I see. Thank you for the answers.

Anyway, do you have any information of the Joseon Princess’ marriage with royalties from another country? I found that was common practice in Three Kingdoms Era.

Thank you in advance.

Although marriage of convenience between Joseon and its neighbouring countries (particularly Ming) was extremely rare (except for the two aunts of Queen Sohye who became the Imperial Concubines of Yongle and Xuande Emperors) unlike its predecessor Goryeo (with its status as Yuan’s son-in-law country), there was one time when Qing tried to exert his influence over Joseon by asking for a Princess to be married off to Qing.

At that time, King Hyojong, who spent his youth as a hostage in Qing himself, received a request from Dorgon, the regent of Qing at that time. Dorgon requested for a Princess to be made his consort, but Hyojong won’t give away his own daughters or his nieces. Hence, a royal relative named Yi Gae-yun offered for his own daughter Ae-suk to be married off to Dorgon, and Hyojong adopted the lady as his princess. Even her title as a Princess is a sad one: conforming herself to a righteous task, Princess Uisun. She was married off to Dorgon in 1950, but Dorgon soon died during a hunting trip. After that, she married Dorgon’s nephew Boro (a practice common to ancient Korean dynasties as well but not Joseon) but her second husband also died shortly afterwards 1952. Her father eventually appealed to Qing for her return and she finally went back, but not to the open arms of Joseon people; they treated her as a worthless person who married the barbarians. Few years after living an agonizing and sad life, she passed away in 1662 at a young age of 27.

Another example would be Princess Deokhye of Korean Empire who was married off to Japanese aristocrat So Takeyuki under the pressure of Japan, but her marriage took place after Joseon/Korean Empire was already annexed by Japan.

Hello! What would happen to the crown princess if her husband died? Would she keep her title or would she lose it? Thank you for all the amazing posts.

Hi Morgan!

The crown princess would be given a honorary title ending with ~bin if her husband happened to pass away before her, and she would receive a posthumous title after her passing. She would no longer be addressed as a crown princess (sejabin) since there would be a new crown prince and crown princess to be installed.

Hello! This made me wonder about the lives of the Grand Princess Consort and Princess Consort. Is it similar to the Crown Princess without certain duties? Thank you for the posts, I had a hard time finding information about the women of the Joseon Dynasty and I really appreciate it!